“I am not bound to win, but I am bound to be true. I am not bound to succeed, but I am bound to live by the light that I have. I must stand with anybody that stands right, and stand with him while he is right, and part with him when he goes wrong.” ~Abraham Lincoln

There is some controversy as to whether this quote is actually from Abraham Lincoln and in today’s artificial everything its nearly impossible to verify but it doesn’t really matter. The spirit of the quote; regardless of whether Abe said it or not is in keeping with what he believed and it is that spirit that moved armies to remain true and to stand with him because they believed he was right.

John McEwan

My great great grandfather, John McEwan was one of those soldiers of the blue who stood with Lincoln although he was a Scot by birth and dearly loved his country. It was this spirit that summoned him from his Scottish home and compelled him to enlist in Lincoln’s army and this spirit that etched his name on a statue of Lincoln on Old Calton Hill in Edinburgh dedicated to the Scottish men who fought for freedom in the US Civil war.

John was born in Blackford in 1833 though there is no record of his birth. His older brother Peter moved to Chicago in the mid 1850s and was a hotelier. John arrived in Chicago on September 12, 1857 to help his brother with the hotel. John had a thirst for adventure though, and was pulled toward a duty he had never sworn to uphold. He enlisted on February 25, 1862 and went into training at Camp Douglas in Chicago. His company, the 65th Illinois Scots Regiment was deployed and was sent on their first battle along with thousands of fresh troops to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia on September 11, 1862 where he engaged in the first battle of his life.

The Union commander, Col. Dixon S. Miles was fresh from commanding during his drunken charge at the Battle of Bull Run fought less than a month earlier. From wikipedia

“Disregarding the advice of his subordinates, Miles divided his 13,000 men into four brigades, with the main force tasked with defending Bolivar Heights, a ridge two miles west of town on the southern bank of the Potomac. Up on Maryland Heights, Miles deployed his weakest brigade, which contained many troops yet to experience combat”.

John McEwan and the Scots Regiment as well as all the troops who trained with them at Fort Douglas were part of this brigade.

The fighting began on September 12, 1862 on the fifth anniversary of John’s arrival in America. It lasted three days and when the smoke cleared, 286 Confederate casualties were weighed against a staggering 12,636 Union troops. Twelve thousand, four hundred and nineteen were either missing or captured. John was among the captured and all were sent back to Camp Douglas where he had trained, only this time as a prisoner.

The Union prison guards treated their fellow troops horribly as they awaited parole that would exchange them for Confederate prisoners and be sent back to the front lines. On October 23rd, riots broke out and many of the prisoners escaped and deserted or were killed. The riots did help to stabilize the deplorable treatment and over the next few months many of the troops were paroled. By December all were paroled with the exception of the 65th Scot’s Illinois Regiment. They were then made prison guards. In ten months, John had been trained at Fort Douglas, captured during his first deployment and made prisoner at Fort Douglas then made prison guard through the winter during which time he contracted small pox that would plague him for the rest of his short life.

On April 13, 1863 John and his comrades were paroled and given furlough. Many left the ranks and deserted never to return. John McEwan turned right around and re-enlisted. Although weak and debilitated from his sickness that never really left him, John and his fellow Scots went on to fight in some of the most infamous battles of the Civil War. From the Programme of the dedication of the Lincoln Statue

“I am requested by Mrs. Margaret McEwan of 61 South Back, Edinburgh to write you, giving you a brief history of John McEwan, now buried at Edinburgh, Scotland. I was in the same company with him. He enlisted as a private. We were known as the “Scotch Regiment”. At first none but Scotch, nor near descendants, being admitted. When he was mustered out in June I think 1865 he was a sergeant. He was a good soldier we had none better … always sober, and always ready for duty. If he knew what fear was, he never showed it. He was in several battles among the number were Harper’s Ferry, 1862, siege of Knoxville, all through the Atlanta Campaign, Columbia, Franklin, Nashville, Fort Anderson (near Fort Fisher) and on up to Raleigh. Colonel Daniell Cameron of Chicago was our first colonel; Walter Scott Steward our second. Captain McDonald was our first captain, James Miller our second … all Scotchmen. We ran out of Scotch before we had filled the regiment and Co I was composed of Germans. John McEwan deserves especial mention for the courage he ever exhibited. I have seen him in very close quarters several times but he never shirked or exhibited a white feather. I would be glad to have his name mentioned as a brave soldier.”

I believe he was there at Bennett Place on April 17th when Johnston’s Army surrendered. John was paroled on July 13, 1865 as the regiment disbanded and returned to Scotland never to again set foot on American soil. His descendants, however would thrive here over the next seven generations and generations yet to be.

Margaret King

Margaret King was born in Edinburgh on September 22, 1843 to parents who had immigrated from Ireland. Not much is known of early life but as many of the young girls and women, she became employed at one of the mills outside Edinburgh. John met Margaret there and wooed her with his stories of the battles of war.

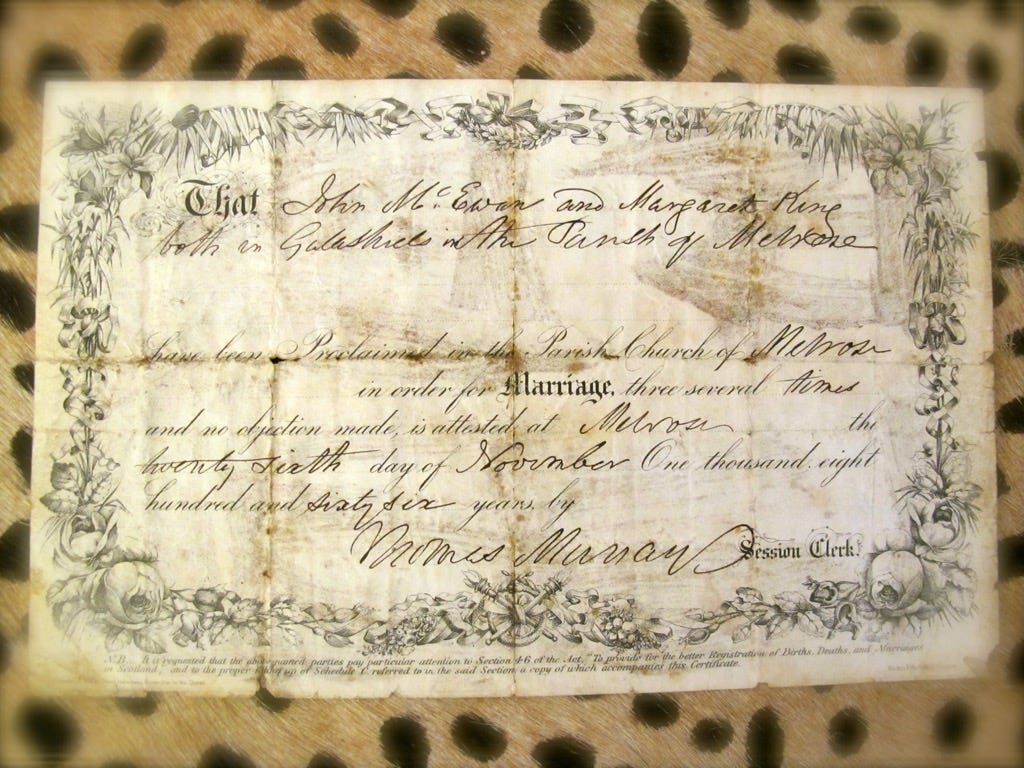

They were married on November 26, 1866

and lived in Galashiels where both of them worked in the mill, John as a weaver, and they started their family. Jeannie McEwan (my great grandmother) was born June 29, 1867 followed by three more girls and two boys. John’s ill health began to affect his ability to work and was able to move a loom into their home so he could continue.

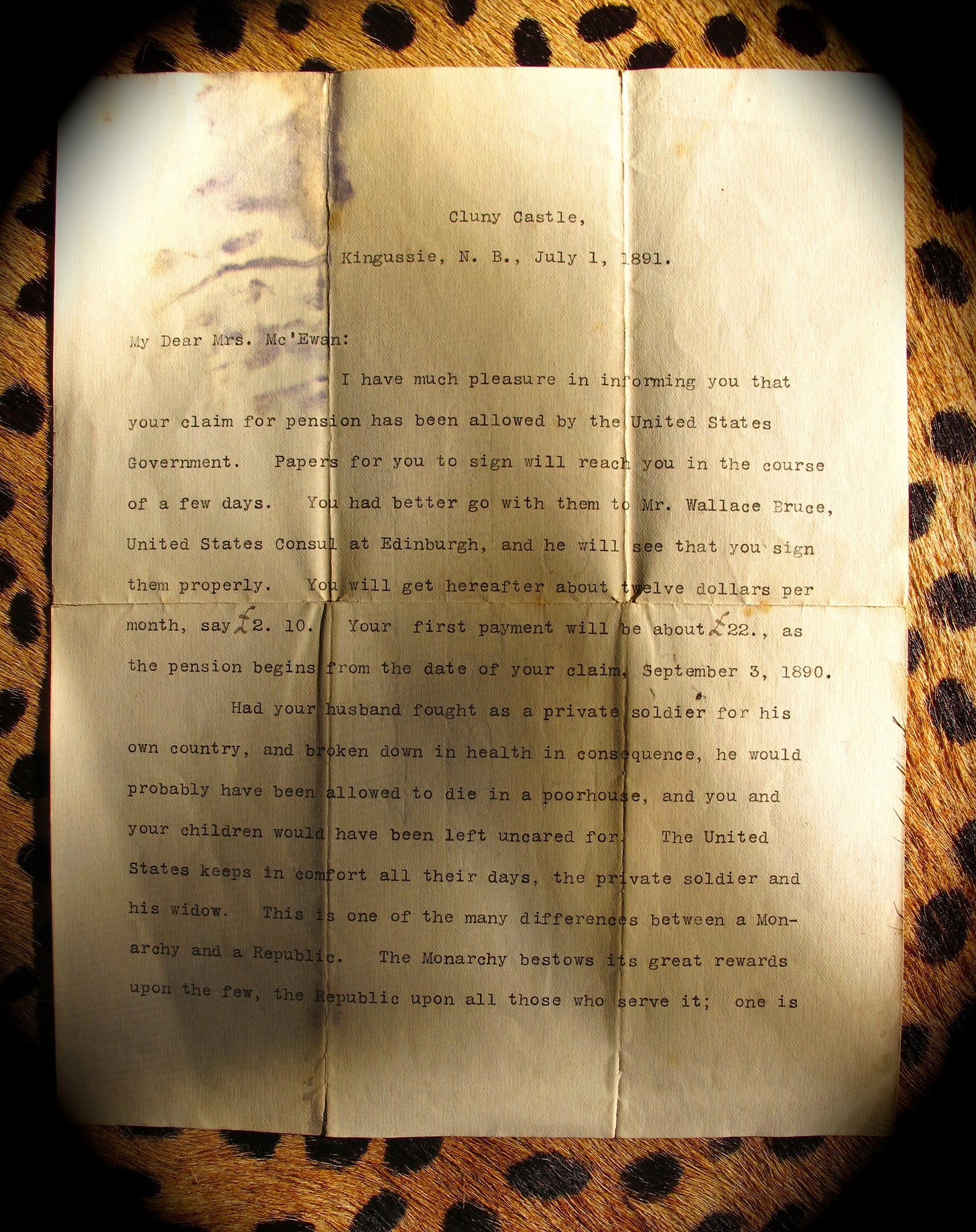

On January 22, 1885 John began appealing to the United States for an invalid pension as he was no longer able to work with four daughters to support. The several attempts made were denied and John passed away on December 4, 18881. Margaret, desperate at this point and fearing having to move into the poor house, began a campaign to collect a widows pension from the United States. The letters I have dated from May of 1891 were finally answered and Margaret was invited to give testimony to the US Consul, Wallace Bruce. April 17,1891. In this testimony it was stated Mrs. McEwan weekly income from her and her children did not amount to four shillings and that all of her property and possessions were sold would not amount to four pounds sterling.

It was in this testimony from Margaret, her reverend and several close friends, one who had made the mourning clothes for the children that Wallace Bruce encouraged her to write to Andrew Carnegie. After the testimony was recorded and witnesses signed and Margaret ready to leave, she was approached by Mrs. Bruce. Prose as it appeared in the programme of the dedication of the Lincoln Monument August 21, 1893:

“Mrs. Bruce chanced to be present, and became interested in her story; how Sargeant Major McEwan wearing the blue army coat with brass buttons, came to the mill in Galashiels where she was employed and how in recesses from work little groups would gather about him as he told incidents of the war. She said she had read “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the poetry of Whittier, which he thought chimed so sweetly with the songs of Burns. THE POET. One day the soldier told the story of his life and won her. Some years afterwards they came with their little family to live in Edinburgh. Sickness entered the household, the father was unable to work. He applied to the Government for a pension, but failed as he was unable to connect his ailment with exposure on the field.

Mrs. McEwan told Mr. Bruce how she and her children had worked for five shillings a week to keep them from the poorhouse and gave with singular pathos the account of his last illness, how he loved to have the old gun near at hand where he could touch it; how he told the doctor on one of his last visits that he had nothing to give him but his sword and the kind hearted doctor replied that it was his business to save life, not to take it and that he wished neither the sword nor any other recompense but pleasant remembrance and the wife said “We will keep the sword for the laddie” and at last when the poor soldier after months of suffering died, then found the gun under the coverlet beside him, pressed close to his heart.

Mrs. Bruce asked where he was buried, that she might go with Mrs. McEwan and place some flowers on his grave, although Decoration Day had passed; but the widow answered, with tears in her eyes: “The ground in the common field is all level; I couldna mark the spot. In fact, the next Sabbath after his death I visited it with the bairns, and we found another mourning group had possession. Another body was being buried in the same grave”.

It was at this moment on May 2, 1891 that would change the course of history. Sparked by Margaret’s story, Wallace Bruce hatched a plan to erect a statue of Abraham Lincoln freeing a slave dedicated to the men who had fought in the war. He took his plan back to the United States and started a campaign to raise money and commissioned George Edwin Bissell to build the statue. In the meantime Margaret anxiously awaited the decision of her appeal to Andrew Carnegie and on July 1st that letter was written by Carnegie granting the pension. This letter has lived in the permanent records of our family and marks the heroic efforts of our ancestors to overcome all odds, to stand in the rightness so deserved by one who fought so bravely.

The dedication of the statue in the cemetery on Old Calton Hill in Edinburgh was held on August 21, 1893.

Bonnie Jean Blackmore

Stay tuned for Episode 2 of Journey to Eden … The Eke Portal

Kin 170 White Magnetic Dog

Very interesting.

Such small tidbits of history that when combined create a mosaic of our past and present.